Fangirling & Fanboying: This Week's Recs from Assignment

Enclosed: Facebook activists, but opposite

Benjamin Nugent -- I’ve used a metal detector to extract a lead .59 miniball from the dirt near Manassas. I’ve sipped whiskey from a party cup at the site of one of the last charges of the Army of the Potomac. I’ve been to the Chancellorsville gift shop and seen the bookshelf that’s divided into three sections: Northern, Southern and neutral. But until recently I was fairly ignorant about what came after the Civil War. So I picked up Black Reconstruction in America, by W.E.B. Du Bois, and The Metaphysical Club, by Louis Menand. Du Bois is interested in the masses: why, he asks, did five million poor whites support a war on behalf of eight thousand rich whites to keep four million blacks enslaved? It’s required reading for the Summer of Trump. Menand is interested is the intellectual foment that attended and followed the war. His book is set in the salons of Cambridge, Baltimore and Chicago. There are characters like Zina Peirce, who believed that adultery should be punished by execution or life imprisonment, and her philosopher husband, Charles, who cheated on her a lot. It serves as a reminder of how hard it is to find role models in the nineteenth century; even the most ardent abolitionists espoused some pretty appalling views. Their heroism resides in what they did, not in what they said. Sort of like Facebook activists, but the opposite.

Eric Beebe -- Ever since reading “The Weirdos,” I’ve grabbed any piece of Ottessa Moshfegh’s work I can. Her short stories fit my tendency to read in twentyish-minute bursts, but when I heard about her novel, McGlue, I had to see what she did with the extra length. The book follows the title character’s inner monologue, picking up where he’s accused of murdering his shipmate and best friend, Johnson. McGlue’s constant state of impairment by both alcohol and head injury keeps clarity to a foggy minimum, and that was perhaps my favorite aspect of the whole story. Being tied to his altered reality, I learned to stop trying to distinguish the corporeal from hallucination and simply accept what he saw in front of him. The dichotomy between these two forces becomes integral to the plot as the weight of events leads McGlue to seek escape by any means necessary, even if it kills him. The resulting feel falls somewhere between reading The Things They Carried and watching Reservoir Dogs while our narrator teeters back and forth between blacking out and drying out. Moshfegh doesn’t hand us just any drunken sailor; she gives us a man floating between two worlds, battling with himself over which to choose, if he can at all.

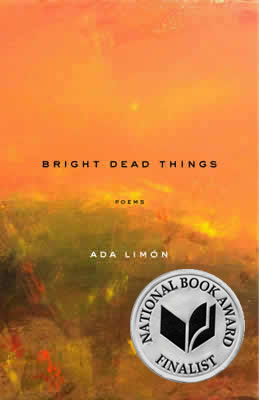

From the cover of Bright, Dead Things

Lisa Janicki -- My favorite poem in Ada Limón’s collection, Bright Dead Things, is “Downhearted,” which begins, “Six horses died in a trailer fire. / There. That’s the hard part. I wanted / to tell you straight away so that we could / grieve together.” She’s a city girl who moved for love to the south, where even the tragedies are foreign. She bumps up against new idioms and “tornado talk”— the subtle stuff that’s peculiar to regions and can be so disorienting to transplants (“All the new bugs.”). And from these small moments, she elaborates larger impressions of her existence. She had imagined herself differently in this new life—more agreeable, more open to its magic, more like a child. But when our grown-up selves allow us to become children again, it’s often in a way that’s less magical and more sullen: in “The Last Move,” she writes, “This is Kentucky, not New York, and I am not important.” I root for Limón as she cleans her big new house and tries to like gardening, though it seems clear she’d rather be in her Brooklyn apartment. I root for her because she threw it all in for love, because she moved to Kentucky for it, because she had no Plan B. And mostly I root for her because I get the sense that she’s resurrected herself before, and she’s about to do it again: “What the heart wants? The heart wants / her horses back.”

David Moloney -- You’d think Olive Kitteridge would be the focus of Elizabeth Strout’s novel in stories titled in her name. But we’re instead given thirteen stories that concern themselves more with the residents of the small, coastal New England town of Crosby, Maine. Olive is a math teacher there, and she seems to have had all the book’s characters in class at one point; she always finds herself crossing paths with them when they’re stalled in a threshold of self-destruction. It’s these characters that are most central to the novel. Whether it’s a former student who contemplates suicide on a beach, an anorexic teen, or even her own husband falling in love with a much younger employee, Olive---through her staunch and sometimes misplaced contemptibility for weak people---says what we’d only wished to have the courage to say. She tells the anorexic girl in “Starving,” after giving sound advice about never giving up, “I know you’ve heard all this before, so you just lie there and don’t answer. Well, answer this: Do you hate your mother?” Olive isn’t always right (sometimes far from it); that’s when the book is at its best. The stories are so human, so New England, and in the closing moments, we know Olive did her best, and we know she never gave up—and isn’t that all we can do?

Nadia Owusu -- I first encountered Lydia Davis two years ago. I was thoroughly confused. What was I reading? Were these monologues? Prose poems? Scenes? “She is the master of the short story,” declared the instructor of my workshop as she assigned three of Davis’s stories to me. “But, where are the stories?” I fretted to myself as I diligently did my assigned reading, certain that I had made some sort of mistake. Don’t get me wrong: I liked what I was reading. I just couldn’t easily categorize it. Later, once my obsessive, ‘I need to make sure I’m doing the assignment right’ voice was quieted by a glass of red wine, I was able to admire the way that Davis was able to imbue such brief moments, untethered by much context or character development or setting or structure, with such feeling and meaning. This month, I worked on my upper body strength by carrying around her Collected Stories. In making my way through it, I tried to give some thought as to how she does what she does and why it works. I found myself particularly admiring how she takes her characters’ specific circumstances and in a matter of a few pages, or in some cases even just a few sentences (Davis’s stories are known for being minimalistic and very brief), makes them universal, raising and exploring difficult questions about the things in people’s hearts and heads that are often heartbreakingly left unsaid.

From the cover of Crimes in Southern Indiana

Ted Flanagan -- Reading Frank Bill’s gut-punch collection of loosely-linked stories, Crimes in Southern Indiana, is to bear witness to a nihilistic muscularity of prose one might expect of the love child of Jim Thompson and Donald Ray Pollock, if such a thing were possible. Bill’s slim collection packs a weight far beyond its pages, delivered at a high-velocity. His characters hint that their squalid, violent lives are the result of choices, often (as in drugs or alcohol or regret) the righteous reward for their own. But also, as in poor teenaged Josephine, who’s own grandfather, Able Kirby, sold her into sex slavery to a local gang—some pay debts incurred by someone else. The opening story, Hill Clan Cross, follows two drug dealers avenging their losses against two associates who got all entrepreneurial with the gang’s drugs, a big no-no in a desolate landscape where the only thing thicker than blood are dollar bills. From there, the book accelerates through the bleakness and darkness until the titular story, the collection’s last, in which Mitchell, a local police detective, attempts to help Crazy, a member of the notorious gang MS-13, which has populated the ranks of workers in a chicken processing factory. For me, that’s the brilliance of the collection. Crimes in Southern Indiana, as it insinuates itself, whispers amongst the brawling, crashing, and exploding backdrop that this isn’t just Indiana. It’s the 21st century Animal Farm, decrying not Fascism, but a distant offspring of it.

John Vercher -- Addiction has a name, and that name is “Scotty.” He’s an incubus and succubus for men and women alike, dangerous in his charm and seduction, fulfilling all cravings while reaping wanton destruction. Scotty is, literally, crack cocaine. He is funny, repulsive and impossible to ignore. In his PEN/Faulkner award-winning novel Delicious Foods, James Hannaham tells the story of Eddie, his mother Darlene, and her relationship with Scotty. It is a story of tragic loss and horrific violence infused with irreverent humor. The novel explores the depths of maternal love pitted against chemical dependence in the shadow of the titular farm where both Eddie and Darlene find themselves held captive. Hannaham’s stark and concise prose is instantly engaging, and doesn’t shy away from the horror of the subject matter while avoiding the melodrama that could easily overcome it. In between the braided flashbacks of Darlene’s youth and the tragic events that lead to her eventual addiction, we’re treated to Scotty’s dark humor and cruel charisma. He’s a twisted conscience in a novel of painful truths about desperate acts and the systematic racism that lead to them. Delicious Foods is at once heartbreaking and breathtaking with richly textured characters that has stayed with me long after the final page.

From the cover of Vitals.

Daniel Johnson -- You've got enough to read (and if you're really interested in what I'd recommend, check out my weekly selections at The Paris Review Daily's "Staff Picks"). Meanwhile, let's talk obscure music. Like many of their fans, I discovered MuteMath when they debuted their first single, “Typical,” on Letterman’s Late Show in the summer of 2007. The band’s performance—and particularly that of drummer Darren King—stunned Ed Sullivan theater such that once the music stopped, all Dave could say was, “How bout that drummer!” Eight years later, in the Fall of 2015—one guitarist, a Transformer’s theme and two underappreciated records since Letterman—MuteMath started its own label, Wojtek Records, and released their first self-produced studio album: Vitals. King’s percussive energy and Roy Mitchell-Cardeńas’ critically acclaimed bass-playing have been at the forefront of most of their music; Vitals, however, is unquestionably frontman Paul Meany’s opus. It’s all vocals, all keys. The result is something like a contemporary eighties record, if only, say, Earth, Wind and Fire had grown up in bluesy New Orleans, where Meany and the rest hail from. Both the album’s single, “Monument,” and “Light Up” share the insane vocal range of “September”; both have that same wedding-reception-banger vibe. And though the album feels at times like a throwback or an homage to Meany's influences (The Police being a big one), it's actually a welcome step into the future for the band: Vitals is heady and joyous and wonderfully hypnotic in a way that most MuteMath is not. Meany has said himself that, when composing a work, he wants the end product to be “a picture of something dark, but it should be framed in light.” This is their first album that’s more frame than picture--just listen to "Stratosphere," my favorite of all eleven tracks: "The sun has lost its gravity / and severed my connection to the starlight. / I never meant to have to start all over / without you."