Interview Assignment: Nadia Owusu discusses grief without borders

What kind of grief follows the loss of the person who was not only your father, but also the only thing that was truly your home?

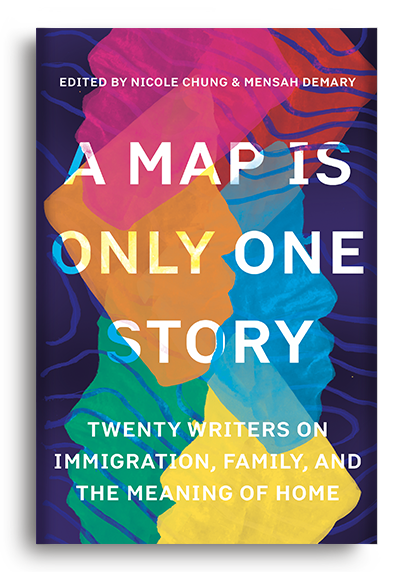

In Nadia Owusu’s essay “The Wailing,” included in the forthcoming collection A Map Is Only One Story: Twenty Writers on Immigration, Family, and the Meaning of Home (Catapult), the cultural fragments of a young life collide when a father dies and a life is irrevocably changed.

Owusu answered several questions over email for Assignment about her essay and her writing as an immigrant.

Assignment: I think many writers with varying degrees of experience often question whether they're in the right place or the correct distance in time from to be "ready" to write about an event. Was there a moment when you felt you were "ready" to write about your father's death?

Nadia Owusu: I certainly understand that need for distance, but it isn’t a need I have, generally speaking. I write to understand: myself, other people, the world. I write through difficult times. That writing isn’t always good. It isn’t always writing I would seek to publish. But, it’s not like writing in a diary—this happened, then that happened. I ask questions of myself about what I am seeing, hearing, feeling. I try to make connections to my own past and to bigger histories. I try to contextualize. And I try to name the unknowns and the things that I am not ready or willing to look at. I’ve been writing essays like this since I was a teenager.

A: As someone who belongs to worlds that are separate yet overlap in some ways, how does language become both a bridge and a barrier?

NO: In a literal sense, language is one of the threads that ties my disparate families together. Everyone speaks English. This is a complicated gift. My Ghanaian and Tanzanian families speak English because of colonization. My Armenian family speaks English because they came to America as refugees fleeing the Armenian genocide. I lived in seven countries before I was eighteen and I picked up several languages along the way: Italian, French, Swahili, Spanish. I speak them with varying levels of fluency. Learning the languages of places where we lived was important to my family. We were interested in connection, in meeting people and places on their own terms and learning from them. I hated the feeling of disconnection that comes with not knowing the language. Growing up as nomadic as I did, there were so many other factors that made me feel disconnected from people and place. It is a great regret that I never learned to speak my father’s language, Twi. I am trying to learn it now.

A: How do you approach the struggle to articulate grief, something that seems to exist somehow either above or beneath language?

NO: Loss and grief are such universal experiences, but they are still somewhat mysterious. Grief is a straddled place between past and future, familiar and unknown. It is a thoroughly irrational kind of longing. We know that the person we love won’t be returned to us, but that is what we want. In writing about losing my father, I am trying to bring him back, even just for a moment, in a sentence.

A: Each one of your sentences, particularly in the concluding paragraphs of the essay, contributes to the raising of certain tension, a kind of manifest effect developed from sorting through the details of total loss. Was this something you purposefully developed during the revision process?

NO: Yes, I did think about tension as I was writing and revising this essay. In the revision process, I paid attention to how the sentences and details accumulated until that final moment of relief. I wanted the structure of the essay to mirror the accumulation of tension in my body at the time.

A: Is the structure of this essay one that developed during the first draft or was it developed in revision?

NO: I had the general structure in mind. This isn’t always the case, but this essay came to me quite whole. My revision process was more focused at the sentence level.

A: The essay weaves together cultural, personal, and historical trauma with enough deftness to not get in the way of the flow of the narrative. What are the challenges of balancing these multiple tributaries that form your singular experience while maintaining clarity and rhythm?

NO: I see the world through all these lenses. In writing essays and memoir, I am very interested in how things came to be, in how the forces of history, politics, geography, philosophy, theology, and story shape the human experience. I often write about these things through my own body, but my story is also the story of my families, the places where they are from, the places I’ve lived, the people around me, the systems that shape our lives. I write from a culture of collectivism. Yet, balance is something I think about a lot. I often write far more material than I use. I go down many rabbit holes, get carried away. This is the fun part. The hard part is asking myself, of the horrible messy draft on my screen, what is this about? Then, I revise. I whittle down, and I ask myself again: what is it really about?

A: What is the best song on Graceland?

NO: You can Call Me Al is my favorite. My father and I used to dance in our living room to that one.

A: Since the stated goal of A Map Is Only One Story is to explore a complex idea of home, how do you feel your experience as an immigrant has shaped your sense of what home is?

NO: I don’t have a home in the sense of a place one can claim in an unambiguous way. I was born in Tanzania, but that was just because my father was posted there by the UN agency for which he worked. My father was Ghanaian, but though I visit often, I have never lived there. My mother is Armenian-American, but her family never lived in Armenia. Her grandparents came to America from Turkey. I am a US citizen, but I didn’t live here until I was eighteen. As a child, I never lived anywhere for more than three years at a time. I lived in Ethiopia, Uganda, England, and Italy. I have lived in New York for all my adult life, so it is a kind of home. But, when I think of home, it is mostly about the people I love. Community is important to me. It’s what gives me a sense of home. I also know how incredibly fortunate I am to have been largely welcomed in all the places I’ve lived. My global upbringing was one of privilege. My father had a UN passport. I have an American one. When I was growing up, families like mine called ourselves “expats.” It is a term that serves to separate immigrants by class, to create a sort of hierarchy. This hierarchy, the belief that some immigrants are more deserving than others, is deeply disturbing. My great-grandparents came here as refugees and made a home for themselves after overcoming enormous obstacles — violence, deaths in the desert, the loss of everything they owned. They made my life, with all its privileges, possible. People are fleeing their homes now for the same reasons my great grandparents fled theirs. It breaks my heart to think that so many are being denied the possibility of making a new home.

Nadia Owusu is a Brooklyn-based writer and urban planner. Simon & Schuster will publish her first book, Aftershocks, in 2020. She is a 2019 Whiting Award winner and both faculty and alum at the Mountainview Low-Residency MFA Program.