Student Picks: Thomas and Gibbons

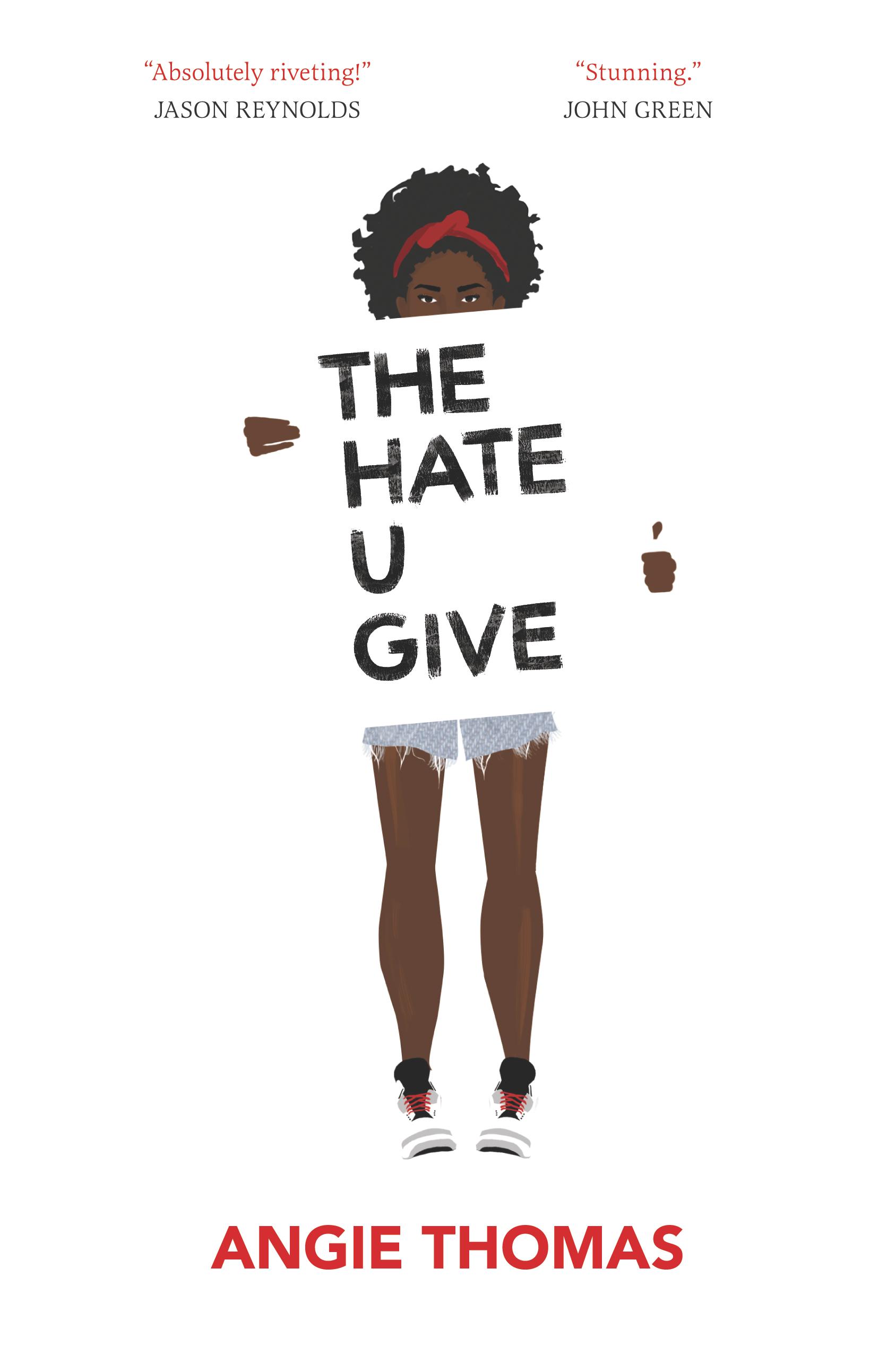

Jemiscoe Chambers-Black-- The Hate U Give, written by Angie Thomas, follows the novel’s protagonist, sixteen-year-old Starr Carter, as she toggles between two worlds: the black impoverished neighborhood where she lives with her parents and brothers, and the wealthy private school in the suburbs.

Starr leaves a party with her childhood friend, Khalil Harris. Starr and Khalil get pulled over by One-Fifteen (nicknamed by Starr from the police officer’s badge number), Brian Cruise, Jr., for a busted taillight. Khalil is manhandled out of his car and then shot three times in the back. Starr becomes the sole witness to his murder and deals with the pressure of having to testify against the police officer to a grand jury.

The truth casts a shadow… people like us in situations like this become hashtags, but they rarely get justice. I think we all wait for that one time… when it ends right.

Maybe this can be it.

These stories are all too familiar, and Angie Thomas doesn’t suddenly decide to give this story the justice that is deserved, tying Khalil’s case with an indictment. That would too easy and not at all realistic. Instead, she stays authentic within the confines of social realism, shining a light on the festering divide of American society and police brutality. The Hate U Give is a young adult book that I recommend for everyone.

Katie Fenton-- I was in search of the perfect piece to read and analyze for the third semester close reading essay, and Kaye Gibbons’ novel Ellen Foster was the recommendation. The story follows the childhood of the narrator herself, Ellen, as she bluntly deals with multitudinous experiences of loss, pain, and torture, as well as the responsibility of raising herself in a world of adults who choose not to.

As a child, Ellen lives with an alcoholic, abusive father and a sick mother who takes her own life in order to relieve herself from her pain and her awful husband. Ellen is bounced from house to house and rejected by her own family time and time again.

Eventually, Ellen finds her escape from this fate, and is able to find out what it is like to truly be part of a family. By no means is Ellen Foster a feel-good novel. However, it is one that profoundly fits into the childhood rhetoric of many of today’s youth. This novel is a worthwhile read and an intense reminder that we’re all just trying to find a place to call ours.